Click Me!

Click Me!

NutmegGraters.Com

- Home

- Featured Stories

- Picture Gallery

- Info.Wanted :

- Spurious Marks

- Trading Post

- Contact Our Site

- Wanted To Buy

[WELCOME: My articles published on NutmegGraters.Com and commercially (elsewhere) required many years of primary research, personal expense, travel and much effort to publish. This is provided for your enjoyment, it is required that if quoting my copyrighted text material, directly provide professionally appropriate references to me. Images are unavailable for copy. Thank you J. Klopfer.]

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The Coquilla Nut Nutmeg Grater

~ Plain verses Ornamental Turning

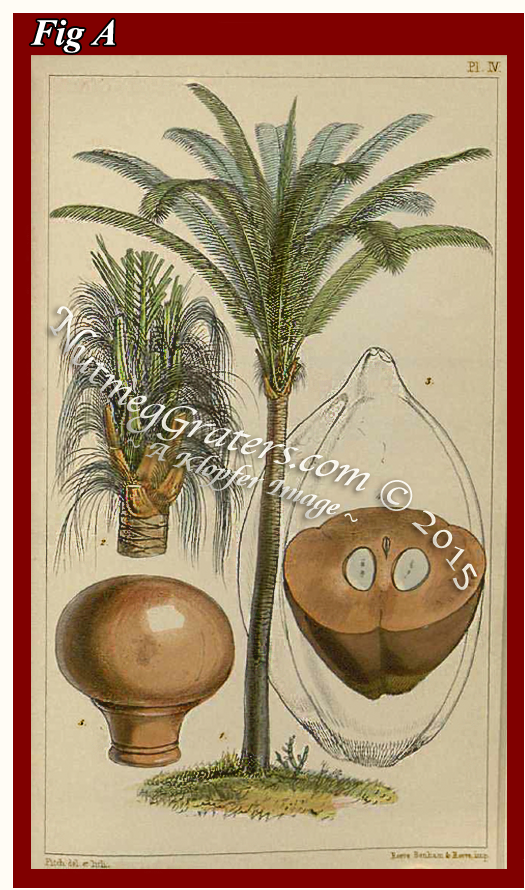

The coquilla nut is a seed pod from a Brazilian palm tree (Fig A). It is well suited to the wood turner's lathe, in that it yields a smoothly polished surface, which is easily fashioned into resiliently hard implements. Notice the coquilla nut to the left (Fig B1) where a top portion was smoothed on a turner's lathe, with a bottom portion remaining in a natural state as found on the palm tree. The nut is nearly solid, with one end indented by two small, bristle-lined cavities (Fig B2). Coquilla nuts were extensively manufactured into buttons, drawer knobs, umbrella handles, bell pulls, small toys and a wide variety of novelty items, to include nutmeg graters.

The coquilla nut is a seed pod from a Brazilian palm tree (Fig A). It is well suited to the wood turner's lathe, in that it yields a smoothly polished surface, which is easily fashioned into resiliently hard implements. Notice the coquilla nut to the left (Fig B1) where a top portion was smoothed on a turner's lathe, with a bottom portion remaining in a natural state as found on the palm tree. The nut is nearly solid, with one end indented by two small, bristle-lined cavities (Fig B2). Coquilla nuts were extensively manufactured into buttons, drawer knobs, umbrella handles, bell pulls, small toys and a wide variety of novelty items, to include nutmeg graters.

The Recency period, figural pear-form nutmeg grater (Fig C1~C3) is turned from coquilla nuts. Notice that the stem at the top (Fig C1) and the calyx on the bottom (Fig C3) are beautifully rendered. Observe that this example is "plain" and free from added ornamental turning. Nineteenth century wood turners report that when lathed, coquilla "admits of an admirable polish and of being lackered." Due to excellent precision threading (a quality inherent to coquilla nuts), both covers of this pear (Fig C2) screw together perfectly. A machine-stamped tin grater is fitted into a ring-shaped, carved-bone housing. This assembly screws neatly inside the top cover. Observe the absence of any wood grain; freckling, seen both inside and out, is a characteristic most notable to the coquilla nut.

Evidence that Dates To 17th Century Europe:

Since the term coquilla is derived from the Portuguese name coquilho, some speculate that early Portuguese navigators were the first to import this seed into Europe. Although historical accounts pertaining to coquilla nut seem unusually absent from European publications prior to 1800, there is evidence that seventeenth century Europe was acquainted with this seed. During recent maritime scientific exploration of late 17th century shipwrecks found on the floor of the North Sea, divers discovered coquilla nuts among the surrounding wreckage. Elsewhere, excavative research at archaeological sites indicates that Dutch manufacturers fashioned "buttons" from the "nut of the Brazilian Attalea funifera palm", dating from the 17th through the 19th centuries. In one written account in 1760, José Antônio Caldas documented that nearly 34,000 "piassava nuts" were exported from the Brazilian Port of Salvador during 1759.

A Botanical Perspective:

Because there are more than 3000 palm species world-wide, it is thought that early botanists had difficulty to decipher the genus of the palm from which the coquilla nut derived, thus little was conclusively delineated. Contradictory names and genus were established; some being published as: A. crassispatha (Plumier 1703); Cocos lapidea (Gærtner, 1788); Lithocarpus cocciformis (Targioni~Tozzette, Circa 1800); Attalea funifera (Martius, 1816); with additional names being ~ Pissata balm; Piassava; Bahia coquilla; Bahia piassava; pissaba palm. Because of this confusion, later publications by nineteenth century botanists make brief reference to past species taxonomies, either reducing historical accounts to a short single sentence, or simply listing several of these early designations without elaboration.

Throughout the nineteenth century, the British government tracked and taxed importation of "Coquilla Nuts, per 1000". In England during 1850, approximately 250,000 seeds were sold for 30s to 40s per thousand count. In 1852, this quantity diminished to 100,000, while roughly 80,000 entered British ports in 1854. By 1872, the media was reporting a demise in stock quality: "The supplies of this, ...[coquilla nut]... from South America have been failing, owing to the indiscriminate destruction of the trees, and the nuts imported lately have been small and immature, and therefore not appreciated and useful."

Snapshots: English Dealers and Manufactures of the Coquilla Nut Products As Seen Through 19th Century Advertisements:

In observing the few surviving advertisements, one learns that coquilla nut novelties were primarily produced in England during the first three-quarters of the nineteenth century:

In observing the few surviving advertisements, one learns that coquilla nut novelties were primarily produced in England during the first three-quarters of the nineteenth century:

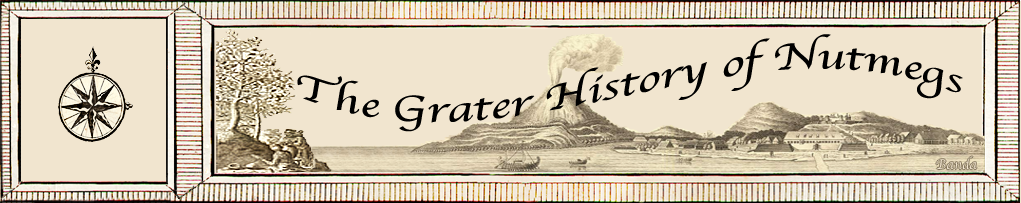

(1). Established in 1732, the Fauntleroy family were long standing merchants in "Foreign Hardwood, Dyewood, & Fancywood" and "Importers of Boxwood, Vegetable Ivory Nuts, &c". They supplied ornamental turners with a large variety of exotic materials. Their advertisements, as seen from the late 1840's through 1870, prominently featured coquilla nuts among their expansive assortment of imported stock. [SEE: 1851 Advertisement.] In 1871, the company ceased operation in bankruptcy.

(2). Rudolph Ackermann (1764~1834) ran a London "Repository" where he marketed fashionable items for ladies. In 1812, he posted an ad within the fine arts section of his ~ Repository of Arts. Literature. Commerce. Manufactures Fashions and Politics; his ladies fashion magazine. The article reads as follows:

"R. Ackermann, having purchased a considerable

quantity of this fruit, which the Portuguese call

Coquilla, the Dutch Coquiletta, but which in

Gärtner's work, De Fructibus Plantarum, bears

the name of Cocos Lapidea, Has converted the

shell of it into a variety of highly ornamental

articles, specimens of which many be seen at

his Repository, No. 101 Strand."

In operation before 1800, Ackermann's store traded in refined art and luxury items. Although he sold articles constructed from coquilla nuts, the type of items and their duration of availability are not known.

(3). John Cole (1792~1848) was a bookseller, author and antiquarian from Lincoln, England. Among his annual catalogs of antique books for sale, he expanded his 1817 catalog inventory of rare books to include several novelty "coquilla nut articles" for sale at his shop. [SEE: 1817 Advertisement.] Cole's ad provided a glimpse of specific coquilla nut items available, but nutmeg graters are not mentioned.

(4). Richard Eyres Eades (1858~1928) was a turner and carver of ivory, bone, hardwood and vegetable ivory whose goods included works in coquilla nut. At the age of 15 or 16, he started his own business at Rheidol Mews. [SEE: 1874 Advertisement.] In 1886, Eades was the subject of a British trade publication article, which further described his craft work:

"IVORY, BONE, AND VEGETABLE IVORY, TURNING, &C.-

At the stand of Mr. R. E. Eades, turner and carver, 30A Wharf Road, City Road, London, workmen will be seen turning and

carving

all kinds of novelties in ivory and foreign nuts. The articles to be exhibited by Mr. Eades include monuments, spires, statuettes,

flower-stands, vases, chessmen, cups, paper-knives, brooches, lockets, billiard-balls, and carving in ivory, generally in ivory, bone,

hardwoods, and vegetable ivory."

Over a twenty year period, Eades attempted to sustain a business as an independent ivory and wood turner in London; yet, engaging in three separate ventures, each initiative resulted in bankruptcy (1876, 1881, 1893). Ironically, nutmeg graters remain absent from listings of his very expansive product line.

At age 48, establishing a more successful business, Eades became an "Automatic Machine" trader. Automatic machines were specialty wood lathes, that when set up, would automatically and repeatedly operate to produce a specific turning or decorative trim. Given his prior work, Eades was well suited to this endeavor. In the 1880's, Richard Eyres Eades had developed his secondary career, becoming a skilled and accomplished photographer. In 1928 at age 68, he died in Edmonton, England, a London suburb.

Although there is no known advertisement or written account specifically listing coquilla nut nutmeg graters, many modern collectors possess them in a variety of forms.

The Manufacturers of the Coquilla Nut Nutmeg Grater:

Based upon inspection of innumerable antique coquilla nut nutmeg graters, one concludes that these nutmeg graters were all produced by one specific, but as yet, unidentified maker. Notice that their basic design, styling, composition of materials, workmanship, and production quality are uniformly replicated across each example.

No documentation pertaining to coquilla nut nutmeg graters is known to exist from any woodworker's shop advertisement, printed product label, manufacturer catalog listing, buyer's receipt or any other written source which might lead to the identification of their manufacturer. In one city alone, Birmingham's 1850 directory lists 80 "Turners in Wood", and 38 "Ivory & Bone Toy and Ornamental Manufacturers". Magnify these numbers of craftsmen throughout Great Britain (or over Europe) while spanning numerous decades and the identification of the actual maker of coquilla nut nutmeg graters becomes like finding a needle in the haystack. Therefore, discovering the woodworking firm that produced these nutmeg graters seems unlikely.

Some general assumption:

~ While various coquilla implements were produced throughout Europe, antique coquilla nut nutmeg graters seem to exclusively trace back

to England: this suggests English origin.

~ Tunbridgeware and woodworking shops in Great Britain were the only firms to include treen nutmeg graters among their general stock:

this likewise implies that coquilla nut nutmeg graters, as manufactured products, are also English in origin.

~ By determining construction methods and technologies utilized during the fabricate of coquilla nut nutmeg graters, a rough calculation of

the period of manufacture can be approximated.

Dating Nutmeg Graters Based on Form:

Sometimes the form or style of nutmeg graters provides meaningful clues when attempting to establish a date or period of their manufacturer.

Turners and carvers often created coquilla nutmeg graters in the form of acorns, buckets and pears (Fig, G, Fig H, Fig C), which are style revivals from earlier periods. Silver acorn shaped nutmeg graters date to the mid-eighteenth century and small silver bucket-form nutmeg graters were most common to the 1790's. The nineteenth century coquilla examples are nearly twice in size, and are only reminiscent to their earlier silver counterparts.

Nearing the turn of the century, pear-form luxury items, such as treenware tea caddies, were made in England and Germany. The pear form continued in popularity throughout the Regency period, Circa 1800~1830's. Although most guess that these coquilla nut pear-form nutmeg graters (Fig C1) date to this Regency period, maybe not; this pear form was later reintroduction by the silversmiths, Thomas Hilliard and Edward Thomason of Birmingham, England. Their highly collectable figural pear-form silver nutmeg graters are hallmark dated from the 1850's through the 1870's [SEE: Robert and Meredith Green Collection of Silver Nutmeg Graters, John D. Davis, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation/University Press of New England, Page 42, 2002].

The method, comparing coquilla nut nutmeg graters with similar silver items in identical forms, provided no support in establishing a period of their manufacture. Due to periodic reintroduction of these popular shapes and forms, no definitive production date was identified based on coquilla nut nutmeg graters forms.

Using Fabrication Styles and Features to Analyze Coquilla Nut Nutmeg Graters:

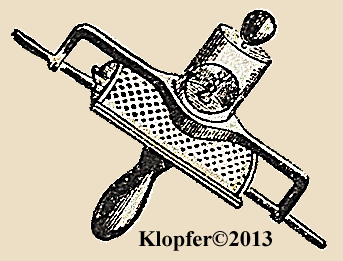

(1). Upon examination, the illustrated grater assembly (Fig D) has a domed shaped tin grater, with machine punched rows of teeth, inserted inside a ring-shaped, lathed-bone housing. The technology to punch-out a tin grater surface (a) in a dome shape and (b) with uniform machine-stamped teeth, evolved in England about 1810. Inspecting a large quantity of this maker's nutmeg graters, the tin graters generally appear as if punched out using the same instrument, being uniform in both size and perforation patterns (usually with 10 teeth crossing the center row tapering to edge rows having only 4 teeth).

Place a half-dozen of these ring-shaped bone grater assemblies together and they appear indistinguishable from one another. Surprisingly, the ring-shaped bone graters are not interchangeable, each being created to counter thread only with its intended cover. This indicates that these grater assemblies were not being mass-produced; a feature in fabrication commonly seen prior to the mid-nineteenth century, probably before 1840.

(2). Although these nutmeg grates are commonly referred to as "coquilla nut", close scrutiny reveals that only some were constructed entirely from the coquilla nut, while others were entirely constructed using imported hardwoods and still others were created with a mixture of both coquilla and wood.

The two novelty table nutmeg graters (Figs E & F) were manufactured using a combination of coquilla nut and "fancy imported" hardwoods. The taller table nutmeg grater (Fig E) separates into three piece (Figs E1, E2, E3). [NOTE: Three different views of the pedestal are shown (Figs E2a, E2b & E2c).] Coquilla nut was used to create the grater on top (Fig E1) and also the top portion of the pedestal assembly (Fig E2a). The cover at the bottom of the pedestal assembly (Fig E2c) is lignum vitæ, and screws into a separate lignum vitæ vessel, created as the container for storing nutmegs (Fig E3). During the early 18th century, lignum vitæ was described as "sweating Medicine", in that it was believed to possess special health benefits. By the 19th century turner praised lignum vitæ because, while beautiful to look at, it was extremely resilient to a turner's lathe.

The shorter table nutmeg grater (Fig F) separates into two piece (Fig F1 ~ F2). The coquilla nut grater on top (Fig F1) screws into a hardwood storage receptacle on bottom (Fig F2). The wood has the appearance and hardness of kingwood, striped ebony or calamander wood [the later described as "very hard, dense and heavy" with coloration of "fine chocolate colour, now deepening almost into absolute black"; reported as first imported into England in the 1820's]. These exotic woods were described among complete listings of imported hardwoods, as discussed within 1830's and 1840's English manuals designated to assist turners and furniture manufacturers. [NOTE: More conclusive examination is needed to confirm that these woods are of kingwood, striped ebony or calamander wood; or some different exotic imported wood in use during that period.]

Although the acorn form pocket nutmeg grater (Fig G) is made entirely from coquilla, the bucket form pocket nutmeg grater (Fig H) and the bottle form nutmeg grater (Fig I) are lathed entirely in the same wood (possibly that of kingwood, striped ebony or calamander).

(3). The distinctive line-etched ornamental turning among this entire group of nutmeg graters is easily recognizable, and an indication that these products are works from a singular turner's shop. Significant advancements in the turner's lathe began during the 1780's and rapidly improved when by 1810, decorative engine turned carving was quickly applied by hand, using an eccentric chuck, and/or revolving cutters.

The unifying element among these nutmeg graters is the line-engraved ornamental etched decoration ~ in a rough guilloche style. Quick tooling yielded slight imperfections and uneven spacing in the ornamentation, which is characteristic to all of these nutmeg graters. The maker applied a dark stain to provide a unified facade and to camouflage the use of differing materials. However, the stain applied to "mixed material" examples, absorbed differently, dependent on the various materials (coquilla being the least absorbent). Observe the shorter table grater (Fig F) noticing that coquilla nut top is lighter and more orange in color than its darkened wooden base.

Should you find information to confirm a manufacturer of coquilla nut nutmeg graters, please let us hear from you!

Acorn form coquilla nut nutmeg graters are readily obtainable by present-day collectors, but table coquilla nutmeg graters are moderately rare. The bucket form example is hard to find and the bottle form nutmeg grater is very rare.

[KLOPFER article © May 2015]