Click Me!

Click Me!

NutmegGraters.Com

- Home

- Featured Stories

- Picture Gallery

- Info.Wanted :

- Spurious Marks

- Trading Post

- Contact Our Site

- Wanted To Buy

[WELCOME: My articles published on NutmegGraters.Com and commercially (elsewhere) required many years of primary research, personal expense, travel and much effort to publish. This is provided for your enjoyment, it is required that if quoting my copyrighted text material, directly provide professionally appropriate references to me. Images are unavailable for copy. Thank you J. Klopfer.]

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Charles Stewart ~ Maker of Small Masterworks In Silver and In Jewelry ~ Active In New York City 1833 Through 1852

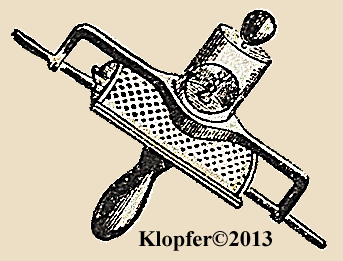

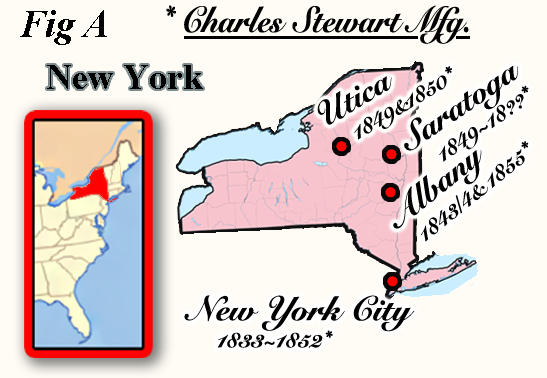

The Stewart family-name is long associated with the jewelry and silverware retail and manufacturing trades, both in Scotland and the United States. Remaining largely obscure and forgotten is the mid-nineteenth century New York City jeweler and silversmith, Charles Stewart (Fig A). Current publications and online accounts about him are nearly nonexistent, and a major primary-resourced investigation was required to unfold the story of Charles Stewart (1805 ~ ? ) and his "Fine Jewelry and Silver Ware Manufactory".

The Stewart family-name is long associated with the jewelry and silverware retail and manufacturing trades, both in Scotland and the United States. Remaining largely obscure and forgotten is the mid-nineteenth century New York City jeweler and silversmith, Charles Stewart (Fig A). Current publications and online accounts about him are nearly nonexistent, and a major primary-resourced investigation was required to unfold the story of Charles Stewart (1805 ~ ? ) and his "Fine Jewelry and Silver Ware Manufactory".

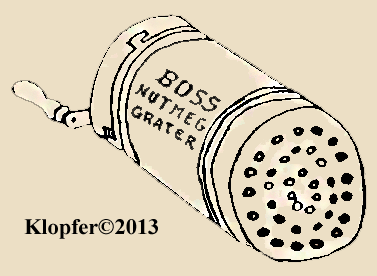

A long-standing puzzlement surrounds a prized silver nutmeg grater in the possession of the Charles C. Williams Collection. Although a sophisticated masterpiece in workmanship and design, when was it made and what of its history? The incuse maker's marked "C. Stewart" is found inside on its lid (Fig B4), yet who was "C. Stewart"?

ASSESSING THE PERIOD OF MANUFACTURE:

At first glance, simple inspection regarding the nutmeg grater's size and ornamental motifs provide helpful clues to detect a period of manufacture (Figs B1-B4) ~

1). PROPORTIONS: Measuring its size at 11.053" H; 2.680" W; 1.815" D. (26.75 mm; 68.07 mm; 46.10 mm), these unusually large dimensions are typical of most silver nutmeg graters produced following 1835, a time when silver-makers created their nutmeg graters to emulate rarity and luxury status suitable for the modern elite, while reminiscent of the smaller pocket graters from prior periods that reflected prominence and social standing. Silver nutmeg graters have always represented sophistication, wealth, and stature; and only the most prestigious nineteenth century silver artisans included nutmeg graters among their wears, thus casting an air of elegance and refinement upon their entire product-lines.

2). ORNAMENTATION: Decorative styling further provides clues to identify the period of production. Both double-layer and cinquefoil roses are sparingly engraved upon both top and bottom covers, and are encircled profusely within a cascading bed of etched feather-foliate scrolls, further embellished by hatch and cross-hatch lines to infuse tonal shading to the scrolling (this specific scrolling pattern is professionally termed "florentine scrolling"). NutmegGraters.Com conducted an exhaustive study pertaining to the history and use of "florentine scroll" decoration, and identified that this styling appears on silver smallwares and boxes date-marked from 1840 to 1861.

2). ORNAMENTATION: Decorative styling further provides clues to identify the period of production. Both double-layer and cinquefoil roses are sparingly engraved upon both top and bottom covers, and are encircled profusely within a cascading bed of etched feather-foliate scrolls, further embellished by hatch and cross-hatch lines to infuse tonal shading to the scrolling (this specific scrolling pattern is professionally termed "florentine scrolling"). NutmegGraters.Com conducted an exhaustive study pertaining to the history and use of "florentine scroll" decoration, and identified that this styling appears on silver smallwares and boxes date-marked from 1840 to 1861.

3). SILVER FINENESS: The Stewart nutmeg grater's total weight is 2.241 ozt (troy oz) [also being the standard weight: 2.462 oz; 44.8 dwt; and 69.7 g ]. Fashioned in "coin silver", the date of construction is prior to 1868 when American silversmiths universally adopted the sterling standard, in competition to English standards.

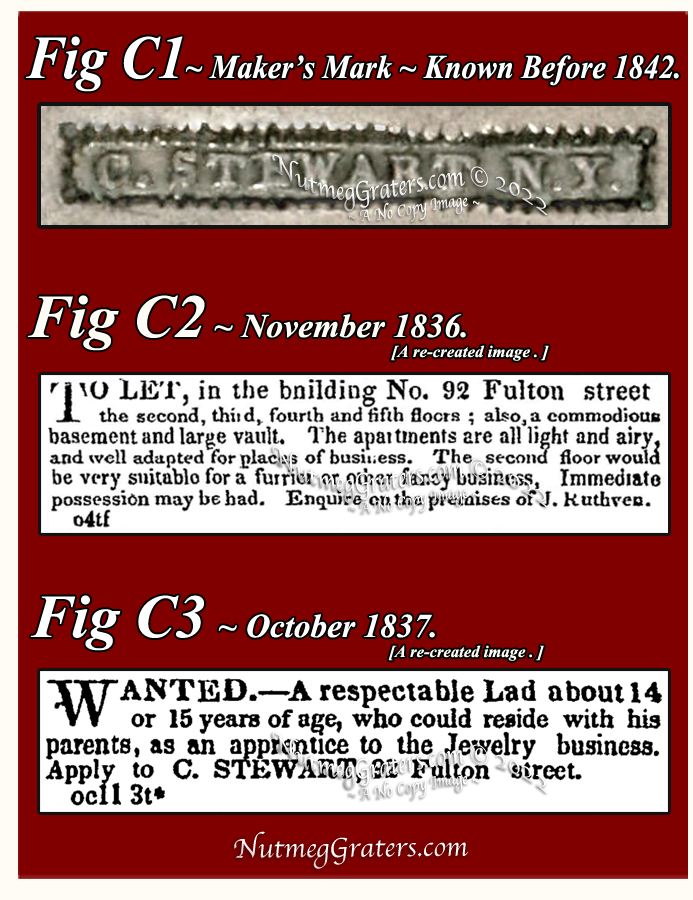

4). COMPARATIVE: Striking similarities to a known and dated Charles Stewart item establishes a more exact production date for this nutmeg grater. A rare octagonal silver cup in possession of The Museum of the City of New York's silver collection bears the identical Stewart's incuse maker's mark as found on the nutmeg grater while also providing an engraved presentation date of "December 12th 1850". [*] [NOTE: The silver cup was a gift from Capt. John Mayher to his unit, the "Tompkins Blues" guards of the New-York State Militia ~ a unit that often "marched in patriotic parades throughout New York State." [7] ] This cup identifies Stewart's incuse maker's mark (Fig B4) being from the late 1840's or the early 1850's, about when Charles expanded his business to 525 Broadway; this mark replacing Charles Stewart's earlier intaglio maker's mark (Fig C1) ~ discussed below. [NOTED ERRATUM: The Museum Of The City of New York's webpage mistakenly provides the birth/death dates (1778 ~ 1869) of Rear Admiral Charles Stewart ~ a different person sharing the identical name. Charles Stewart, the silversmith of New York City, was born in "New York" in 1805 (his death records are yet to be located)].

5). ADDITIONAL INFORMATION: Of oval form, the C. Stewart silver nutmeg grater's lid fastens in back using an elaborate stand-away hinge and its lid opens by means of a simple cast silver thumb-tab applied in front. The florentine scroll engraved decoration is framed within planish-band edging. In the center of the lid, the owner's initials "E.C.A." are monogrammed using a "Gothique Anglaise" font {as termed by: Jules Girault}. Inside is a decoratively punchworked metal rasp that complements the external florentine scrolling; the rasp is rimmed within a silver collar, hinged internally to one side and retains its original protective bluing added to ward-off any potential rusting. To easily access the stored nutmeg housed underneath the rasp, a small cutaway in the grill-frame accommodates the user to easily lift one end of the hinged rasp from within its frame. The maker's marked C. Stewart (Fig B4) is located on the underside of the lid.

Based on design elements, its production date is established between circa 1845~55. From genealogical data, this nutmeg grater was likely a product from 1849~50, when Charles Stewart opened his 525 Broadway retail "BRANCH" in New York City. This beautiful nutmeg grater is a small masterpiece in silver.

WHO WAS C. STEWART?:

The Stewart family name has long association with refined fancy goods, jewelry and silverwares, first in Scotland and later, in America. Among early American silversmiths of the 18th and 19th century, many "Stewart" names are randomly listed within publications. While most are listed by name-only with no identified maker's marks, the literature features a few with their marks. Of interest among the American Stewarts with identified maker's marks, these manufacturers (makers) and retailers all use similar Roman Capital font intaglio marks to identify their wares. This study collected the following American names: John Stewart, New York City & Baltimore [2, 4, 6 & 10]; C. W. Stewart, Lexington, KY [2]; Charles G. Stewart & George L. Stewart, Charleston, VA [10]; George W. Stewart, Lexington, KY [10]; Arther Stewart, Baltimore MD [4]; Charles H. Stewart, Easton, MD [4]; George O. Stewart, Baltimore MD [4]; James Stewart, Baltimore MD [4];

and also included, is Charles Stewart of New York City.

CHARLES STEWART, A NEW YORK CITY SILVERSMITH:

Stewart is an obscure, but prominent mid-nineteenth century New York City jeweler and silversmith. This study begins with little more than his "C. Stewart" maker's mark from four silver objects. Until now, scant evidence or published information portray anything of this artisan. NutmegGraters.Com launched an extensive investigation to uncover the identity of Charles Stewart. Here is his story:

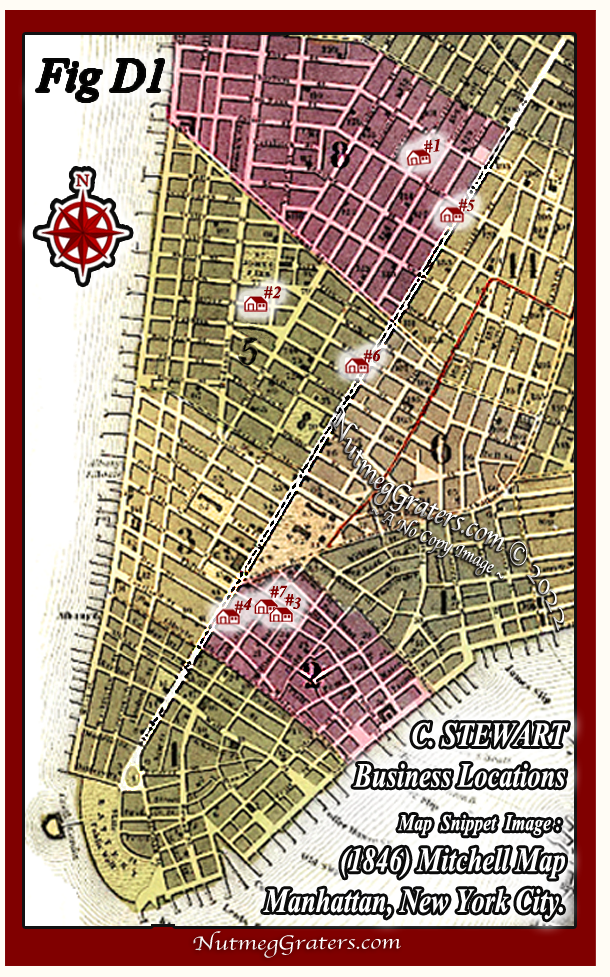

Born in "New York" in 1805, it remains unknown where Charles Stewart lived as a child, who his parents were or how he acquired his trade. [NOTE: Based on this time-line, however, the silversmith John Stewart of New York City and Baltimore seems a potential familial relationship, which is suggested for further research consideration.] Charles first appears in New York City in 1833 as a 28 year-old jeweller whose business begins for one year at 100 Wooster Street, Ward 9 (Business #1: Fig D1). In 1834 until 1836, Charles relocates his jewelry shop six block south at 32 North Moore Street, Ward 5 (Business #2: Fig D1), where he resides nearby.

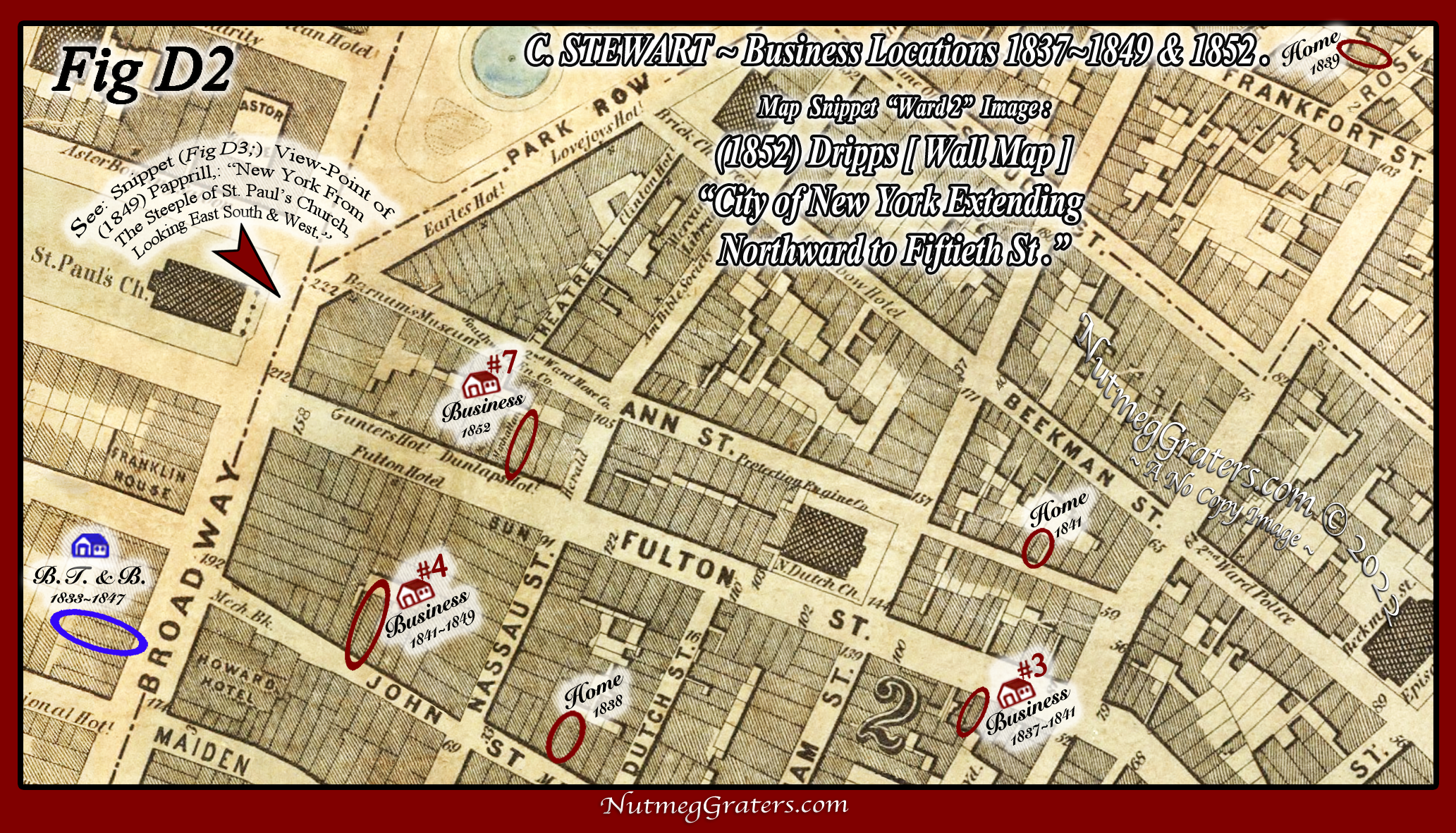

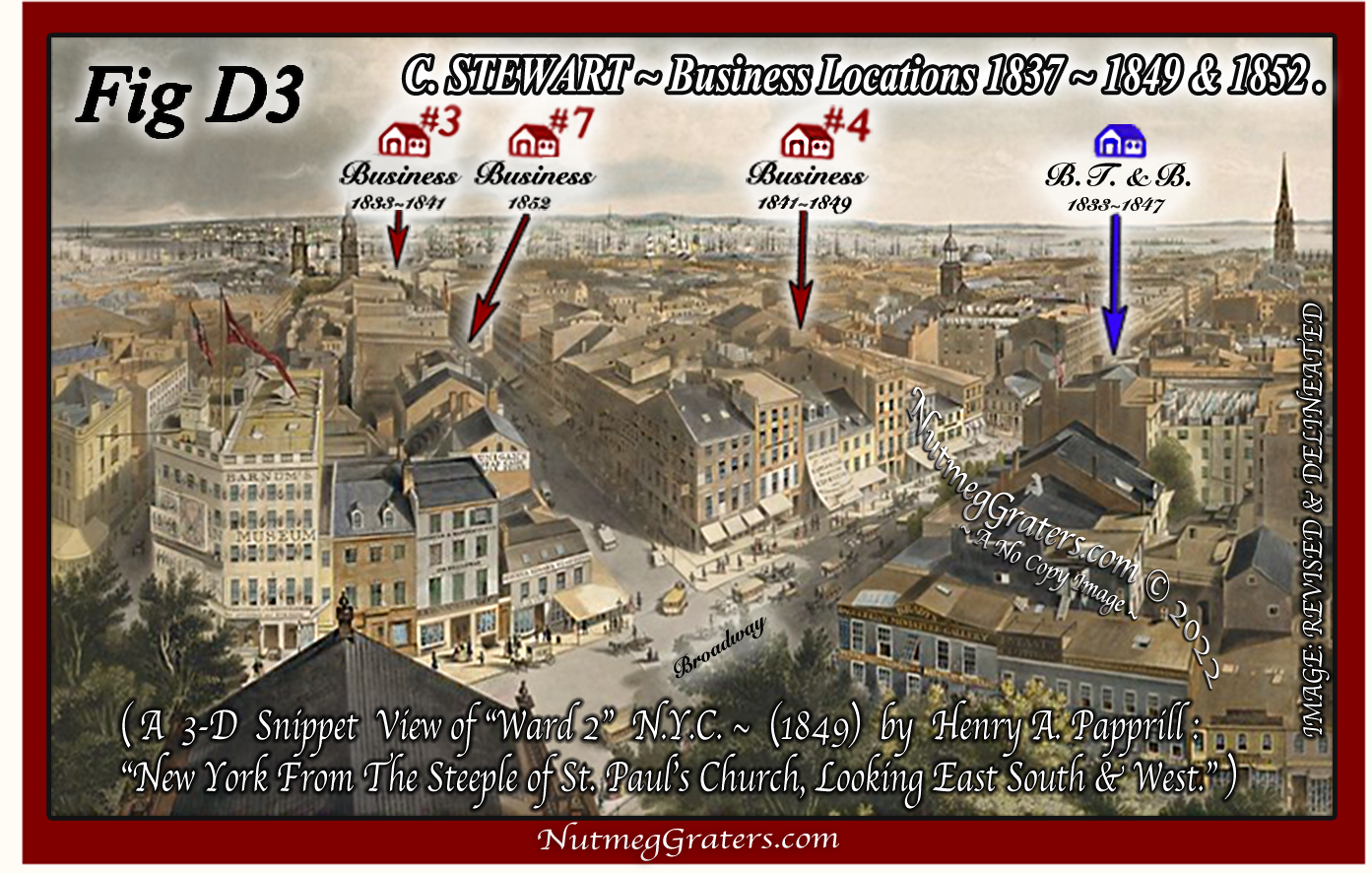

In November 1836, the draper John Ruthveu published a newspaper ad (Fig C2) seeking commercial tenants for his "…building No. 92 Fulton street; the second, third, fourth and fifth floors…", where "{t}he second floor would be very suitable for a furrier or other fancy business." Ruthveu's building was in the heart of Ward 2 ~ then, New York City's preeminent manufacturing and trade center, sometimes described as N.Y.C.'s "metal trade district", including businesses dealing in rare metals such as gold and silver. In 1837, Charles Stewart relocates here, subletting the second floor. (Business #3: Figs D1, D2, & D3). That Fall, Stewart ran local newspaper ads (Fig C3) seeking "an apprentice" ...to... "apply to C. Stewart 92 Fulton street." Charles' business would remain at this location for a period of four years until 1841, although his home addresses changed annually [As Illustrated: (Fig D2)]. In 1841, Stewart once again moves his manufactory, this time to a larger space at 13 John Street, a more prominent address (Business #4: Figs D1, D2, & D3). Stewart was only one of several commercial tenants in the building and his "upstairs" location included a separate owner's living quarters. This location remained Charles' New York City home and main factory address through 1849. [NOTE: Periodically during this time, Stewart is also listed having multiple home and/or business addresses that seem randomly located in other cities of Albany, Saratoga and Utica, New York. These additional addresses are inconsistent, fleeting and variable, suggesting periodic attempts to enhance his business ventures.] Charles' 13 John Street manufactory is 5-doors off Broadway, a location bustling nearby with people drawn to the City Hall Park & Gardens, Barnum's Museum, St. Paul's Church, area first class hotels, and high-end shops. Of key importance is Stewart's close proximity to Ball, Tompkins & Black (SEE: B.T.&B. in blue [Active Under This Name 1839 - 1851]: Figs D2 & D3). Ball, Tompkins & Black is the famous jewelry and fancy goods store located during this period at 181 Broadway and their business connection originally drew Charles Stewart to relocation in Ward 2.

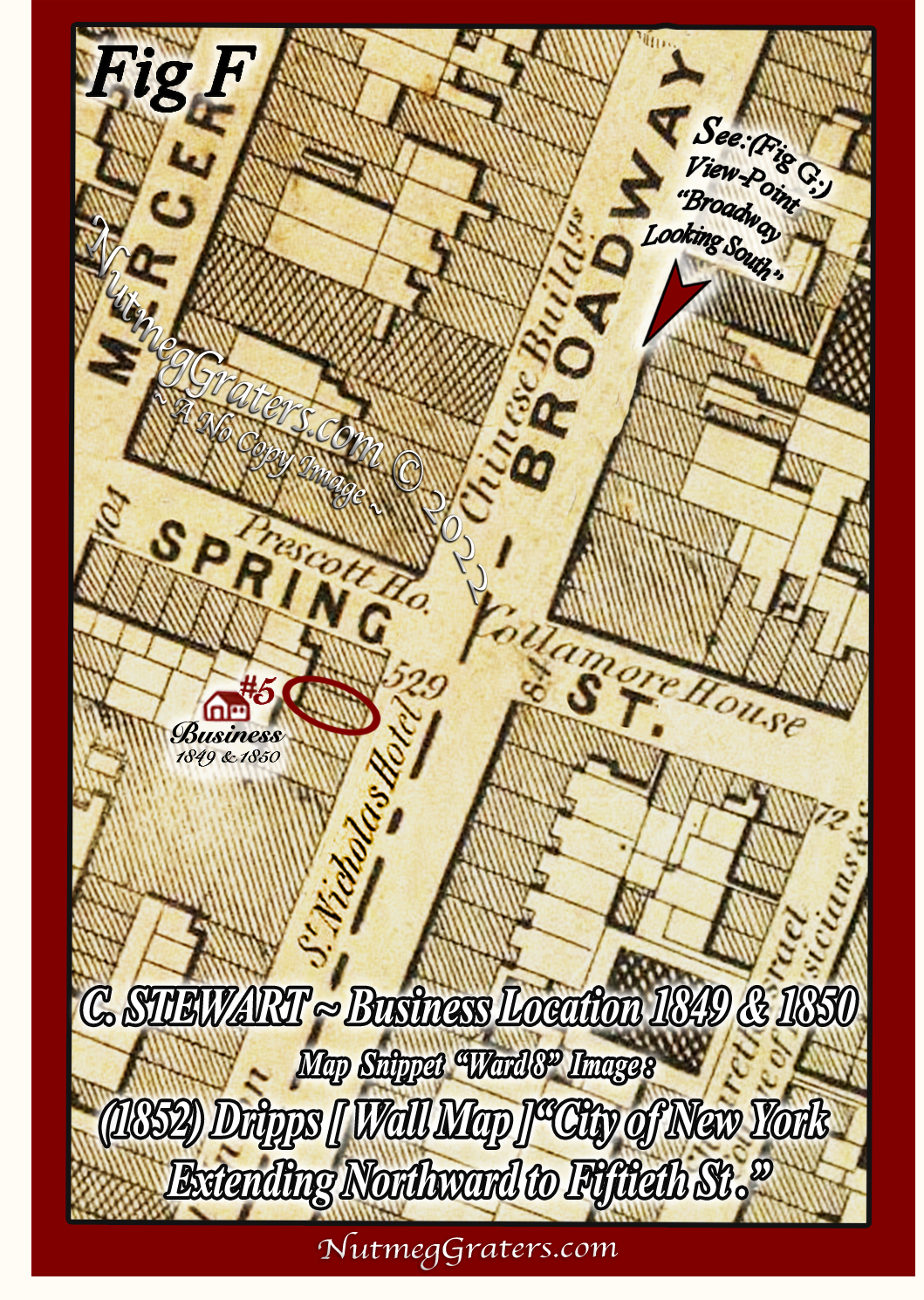

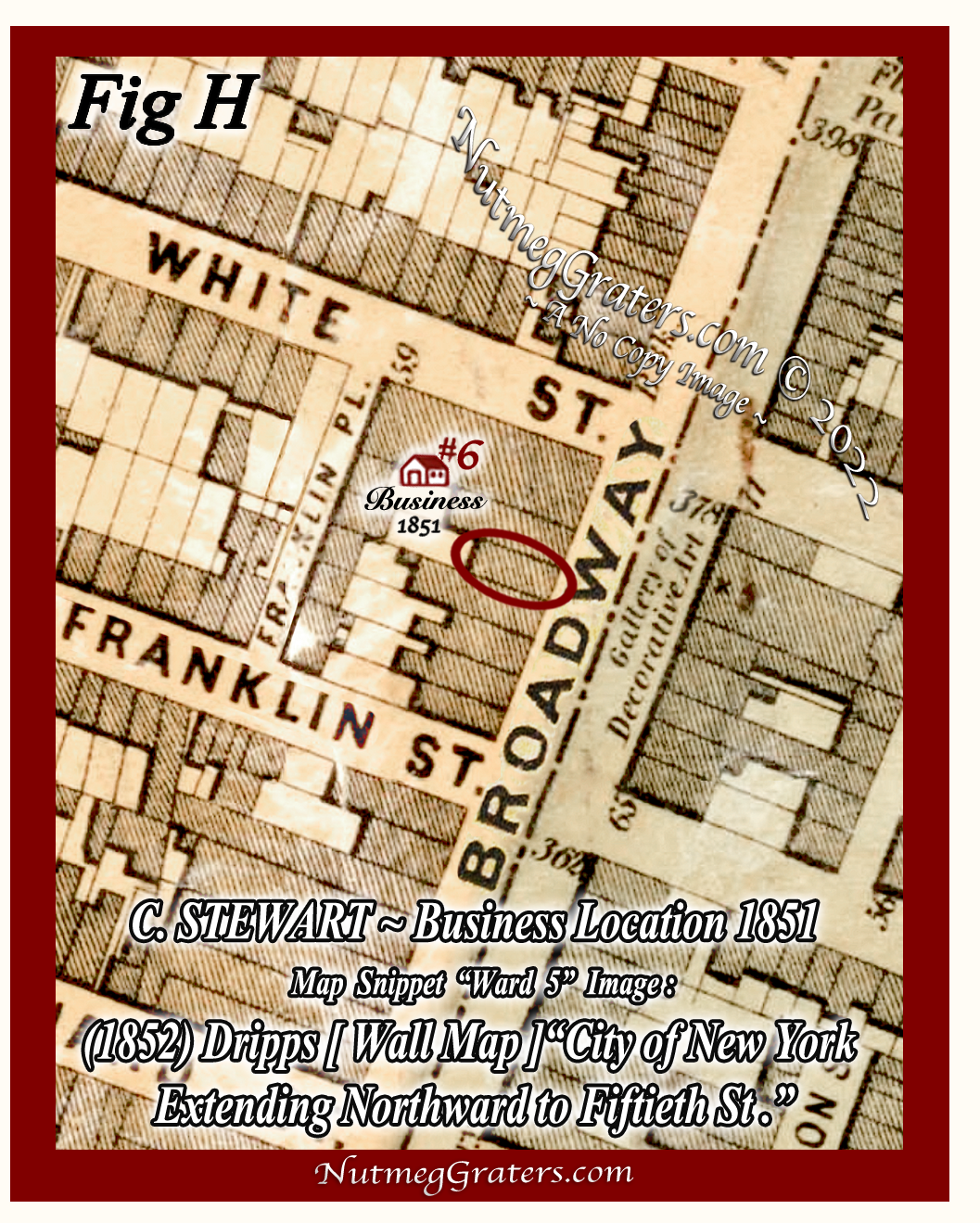

[Exact address locations (Fig D2, F &H) were accurately determined by cross referencing M. Dripps, City of New York Extending Northward to Fiftieth St. [Wall Map] (1852) with Doggett Numbered Street Business Directory (1851); while also consulting New York City Residential and Co-Partnership Directories as secondary resources.]

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Elite Victorian-era New York City shoppers rarely strayed from Broadway to retail stores located on its side streets. Due to the lack of customer support, these retail enterprises, even when only the first or second storefront off Broadway, regularly struggled and often failed. Stewart's locations, first at 92 Fulton Street and later at 13 John Street, are both off-Broadway, an indication that his primary business was not in retail sales.

Elite Victorian-era New York City shoppers rarely strayed from Broadway to retail stores located on its side streets. Due to the lack of customer support, these retail enterprises, even when only the first or second storefront off Broadway, regularly struggled and often failed. Stewart's locations, first at 92 Fulton Street and later at 13 John Street, are both off-Broadway, an indication that his primary business was not in retail sales.

Within the 1833 to 1836 N.Y.C. directories, Stewart's occupation is listed only as a "jeweler", but when in Ward 2, his business expands to include the "manufacturing" of fine silver. From 1837 to 1849 Stewart developed his business as a "Fine Jewelry And Silver Ware Manufactory" and Stewart appears as an independent subcontractor primarily marketing to retail businesses (until later in 1848/1849).

When in 1841 the international attraction Barnum American Museum opened at the corner of Broadway and Ann Street, the next year 1842, Charles relocates two blocks south at 19 John Street. Evidence shows that Stewart manufactured products for the nearby and newly renamed retail store Ball, Tompkins and Black at 181 Broadway ( [At this location, priorly named Marquand & Brothers,1833; and Marquand & Co., 1834~1839] ~ SEE: Fig D2 & D3 ~ B.T. & B) [9]. Stewart's earlier "C. Stewart NY" maker's mark (Fig. C1) is documented in conjunction with Ball, Tompkins and Black and dates prior to 1842. Stewart is a "manufacturer"[5] intertwined as a colleague, working in affiliation with "Ball, Tompkins & Black"[5], "William Forbes" [5] and an unidentified maker who relocated from N.Y.C. to Upstate N.Y.[5] (possibly Charles Brewster Jr.)[6]. The duration during which Stewart utilized his early intaglio "C. Stewart NY" mark (Fig. C1) remains uncertain, but by 1848/1849, that mark is replaced using a more modern incuse "C. Stewart" mark (Fig B4). No images for any location of Stewart's businesses nor the Ball, Tompkins & Black store at 181 Broadway are yet known. However, a famous print by the prominent English aquatint-style engraver, Henry A Papprill (1817~1896) captures the essence of Ward 2 at Broadway in 1849 [Engraving Title: "New York From The Steeple of St. Paul's Church, Looking East South and West" (1849), Publisher: H. J. Megarey, New York ~ SEE: Snippet View (Fig D3).] This area along Broadway was an internationally thriving and fashionable location during the 1830's and into the early 1840's. This would soon change; so too would Charles Stewart's affiliation with "Ball, Tompkins & Black".

NEW YORK CITY'S NORTHWARD EXPANSION:

The 1840's begin a new Gilded Age, when the tastemakers of New York defined the developing American landscape of luxury. Manhattan ushered in its virgining period of unbridled wealth thus leading to the new "American Renaissance".

By 1846, a new wealthy elite of New York began building opulent and exclusive residences in Ward 15 adjoining Washington Square. Northwardly above 14th Street, sparse building still existed and the highly detailed 1852 map by Dripps & Harrison ends its boarder at 50th Street because to its north, row after row of streeted-blocks remained largely uninhabited. At this time, a large park north of 50th Street was only a "proposal" [now known as Central Park, it was not approved until 1853, and opened on tiny scale only in 1858].

In 1848, Ball, Tompkins & Black, and Charles Stewart are no longer intertwined as business colleagues. Ball, Tompkins & Black relocated five blocks northward in Ward 2 to their new store, across from City Hall and City Hall Park, at 247 Broadway on the corner of Murry Street[9]. While Stewart maintains his "Manufactory" at 13 John Street, late in 1848 or by early 1849 he opened a new retail "BRANCH" jewelry and fancy-goods store, 21 block to the north in Ward 8, at 525 Broadway near Spring Street (Business #5: Figs D1, F & G). This was a time when affluent shoppers began abandoning lower Manhattan, instead frequenting the newly erected and more fashionable Ward 8 shops, where Charles Stewart had opened his retail store.

During the years 1849 and 1850, staff managed Stewart's New York City business operations, while Charles relocates his residence to Utica, New York, where he joined with Jacob Guinguigner (1795~1853) and his wife Emma. Guinguigner manufactured new watches and serviced "watch repair" for his own business in Utica, as well as for Stewart's New York City business. Guinguigner had emigrated from France to Utica about 1840 and upon arrival is first listed as a "watch repairer". By 1844, Jacob had opened his own "watch and jewelry store" at 162 Genesse Street, together with Emma's "millinery store". [NOTE: The 1849 and the 1850 Utica City Directories list the Stewarts and the Guinguigners with neighboring addresses, but the 1850 U.S. Census {conducted June 1850} list both families, all 10 members, living together with Charles named as the head of household.] The Utica City Directories only provided the Stewart family's local residential street address and Charles' occupation as a "silversmith", however, the directories omit any mention of his business location. [NOTE: This was a method commonly used in directories of that time, indicating when a resident's non-local business location was elsewhere; in this case N.Y.C.] During the summer of 1849, Charles and his wife Ann celebrate the birth of their son, Robert. It remains unknown why Charles Stewart relocated to Utica or why he resided there for only 2 years before leaving by 1851. Was he expanding business? Was it because Guinguigner might be ill? Jacob Guinguigner died in Utica in 1853 at the age of 58.

During the years 1849 and 1850, staff managed Stewart's New York City business operations, while Charles relocates his residence to Utica, New York, where he joined with Jacob Guinguigner (1795~1853) and his wife Emma. Guinguigner manufactured new watches and serviced "watch repair" for his own business in Utica, as well as for Stewart's New York City business. Guinguigner had emigrated from France to Utica about 1840 and upon arrival is first listed as a "watch repairer". By 1844, Jacob had opened his own "watch and jewelry store" at 162 Genesse Street, together with Emma's "millinery store". [NOTE: The 1849 and the 1850 Utica City Directories list the Stewarts and the Guinguigners with neighboring addresses, but the 1850 U.S. Census {conducted June 1850} list both families, all 10 members, living together with Charles named as the head of household.] The Utica City Directories only provided the Stewart family's local residential street address and Charles' occupation as a "silversmith", however, the directories omit any mention of his business location. [NOTE: This was a method commonly used in directories of that time, indicating when a resident's non-local business location was elsewhere; in this case N.Y.C.] During the summer of 1849, Charles and his wife Ann celebrate the birth of their son, Robert. It remains unknown why Charles Stewart relocated to Utica or why he resided there for only 2 years before leaving by 1851. Was he expanding business? Was it because Guinguigner might be ill? Jacob Guinguigner died in Utica in 1853 at the age of 58.

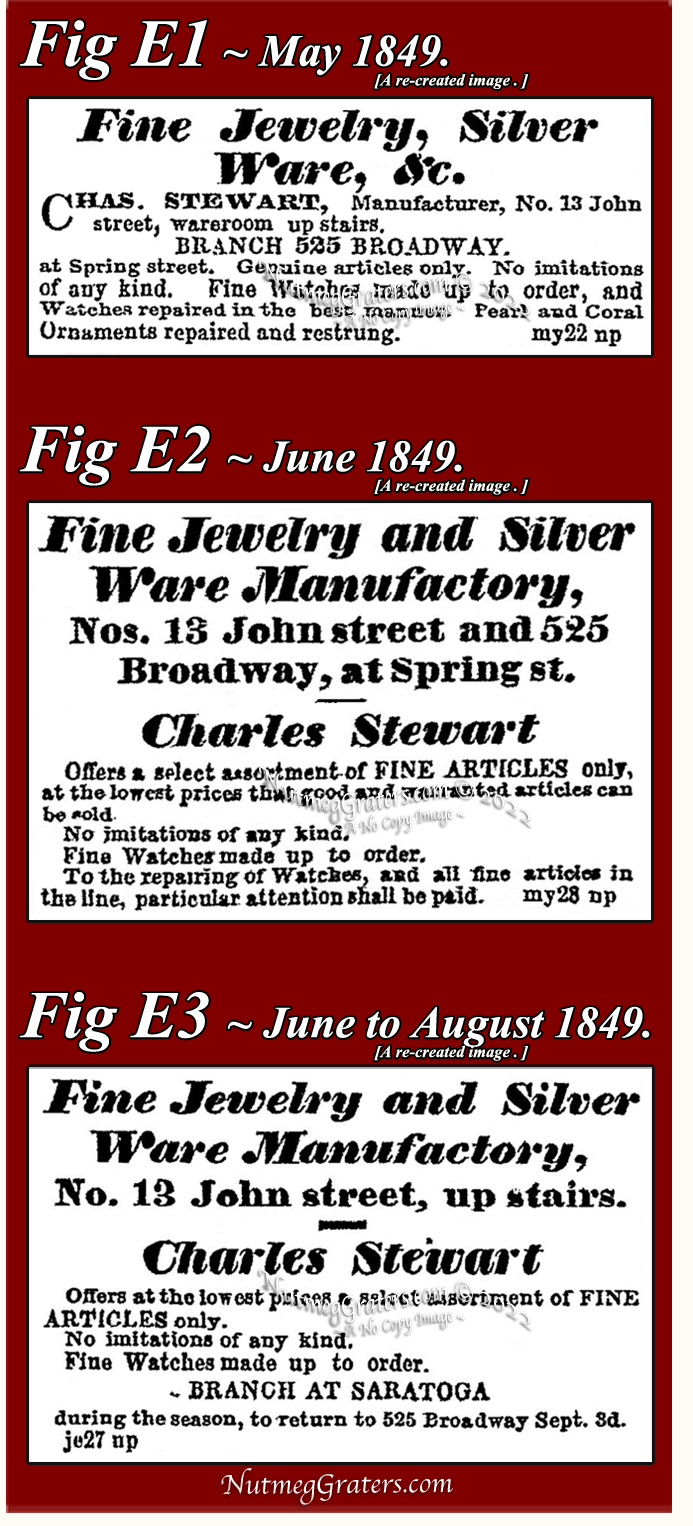

In New York City, the 525 Broadway "BRANCH" was situated three buildings south from Spring Street (Fig F), being near the Prescott and Collamore Hotels and neighboring the newly planned St. Nicholas Hotel. In 1849, Charles ran series of retail newspaper ads drawing attention to his newly expanded "Fine Jewelry and Silver Ware Manufactory". Each ad highlighted the "Manufactory" at 13 John Street, and each included reference to Guinguigner's "Fine Watches made up to order" (Figs E1, E2 & E3). A final series ran late June through late August (Fig E3), indicating that the 525 Broadway location was closed "during the {...summer...} season"; the time when the upper class excursioned away from Manhattan's heat. The advertisement indicated that the New York City shop would re-open "Sept. 3d", while also announcing another "BRANCH AT SARATOGA". NutmegGraters.Com was unsuccessful to locate evidence substantiating the Saratoga "BRANCH", suggestive it was a brief endeavor. During this period, Charles Stewart seemed scattered between several residential and business locations.

From the N.Y.C. Directories, we conclude that the 13 Johns Street "manufactory" was closed by 1850 and that the 525 Broadway "BRANCH" was Stewart's sole location remaining in operation in N.Y.C. It is uncertain if Stewart condensed his "manufactory" to 525 Broadway, or relocated it elsewhere up-state? In either case, a more pressing problem seems to emerge in that Stewart's 525 Broadway business was located squarely within the path of the proposed expansion plan for the St. Nicholas Hotel (Fig G).

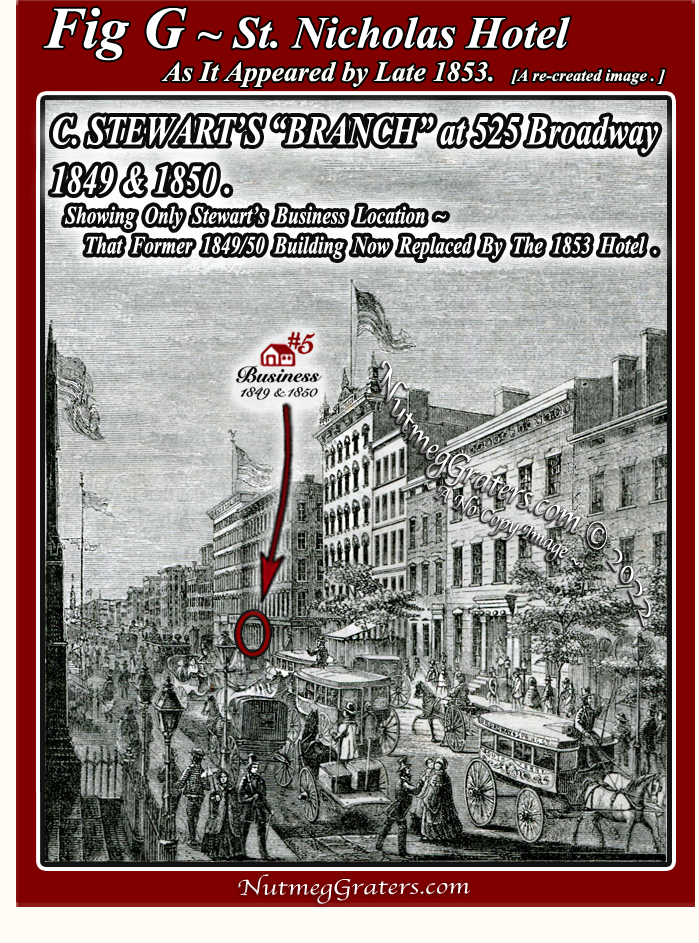

It was about 1850 when capital investors initiated plans to build what became the famous St. Nicholas Hotel. The hotel was built in two separately constructed sections; conjoined structures completed more than a year apart. The finished project covered the entire northern two-thirds of the city block along Broadway, Spring and Mercer Streets (this included Stewart's business location). The first section of the hotel stood in the middle of the block at 515 Broadway, running 100 feet north from Broome Street and 100 feet south from Spring Street. This construction was well underway by 1851 [the 1852 Dripps map snippet (Fig F) shows this first section layout completed]. The hotel's second section would encompassed the remainder of the block to the north, running the length of Spring Street, including where Charles Stewart's "BRANCH" store had continued in operation at least through 1850. No doubt that the St. Nicholas Building Association was buying any available property within this area, but they were unsuccessful to secure the entire footage until April 1853 when the building association leased the remaining obstacle, acquiring the two corner lots from the Kipp estate in an extended lease agreement. How and when they acquired Stewart's location is unknown. Nor is it know if Stewart owned or leased his business property.

The St. Nicholas Hotel was the result of powerful, big business. The hotel's design was revolutionary in every imaginable way, being compared with the finest hotels of London and Paris. One major development was its introduction of retail stores at the street level. Never seen in prior hotel buildings, this was a new innovation designed to attract elite hotel patrons to shop at these high-end markets. The hotel's street level stores were open for business in early 1852, and began running newspaper "sales" ads on April 4th that year. These businesses opened nearly an entire year before the hotel's official opening. The hotel's first section was not formally opened until January 6, 1853, after which the New York Times reported: "This magnificent establishment, which in extent of accommodation, completeness of arrangement, costliness and chaste elegance of decoration, and combination of all modern improvements, takes place as the Hotel par excellence of our day." (January 7, 1853, Page 6). The Spring Street section of the hotel was not completed until May 1853, and a final portion on the south side in June 1853. The corner at Broadway and Spring Street became "the destination" in New York City for wealthy world travelers, with special transportation linking this area to every port of entry and all train stations. But, what happened to Charles Stewart?

Neither the 1851 New York City Directory nor the 1851 Utica City Directory included mention of Charles Stewart; ~ not by his name, occupation nor business or home addresses. Stewart seemed to have vanished. Only within a more obscure Doggett's New York City Street Directory, 1851 [a publication that canvases and inventories occupants according to their street name and then by their street number] is Stewart's business listed, being among Broadway occupants at "375" ~ "Peter Roberts, fancygoods; Charles Stewart, jeweler" (Business #6: Figs D1 & H). Well before and long after 1851, Peter Roberts was an "importer of lace and embroideries" at this business address. Had Charles Stewart simply established a retail outlet randomly at this location? Or, was the "milliner" Mrs. Emma Guinguigner of Utica and Peter Roberts of N.Y.C., each being of similar vocations, somehow connected, thus explaining why Stewart's business relocated here? Regardless, Stewart's business listing at this location was only for a single year.In 1852, Stewart is last listed in New York City as a "jeweller" at 131 Fulton (Business #7: Figs D1, D2 & D3), the address of the small Stoneall Hotel in Ward 2. It was common practice for small 19th century manufacturers located outside New York City to maintain hotel accommodations within the city to conduct business and market their manufactured goods. Observing this hotel address, had Stewart set up operations somewhere in Up-State New York? Was he now working in a very reduced level of business, making small scale jewelry from a small hotel? Or, was his business coming to an end? Had Charles entered employment as a silversmith, working for another firm? An extensive search found that after 1852, Charles Stewart's name never again appears in New York City, nor is his business found elsewhere. Only once in 1855 does the Albany City Directory {New York} list "Charles Stewart, silversmith, bds Eagle tavern", after which Stewart seems to completely vanish from all records ~ or, at least for now.

Sadly, Stewart's failed attempt to successfully relocate a sustained high-end, uptown retail business at 525 Broadway was followed successfully by his rivals. In 1854, Tiffany, Young & Ellis removed from 271 Broadway becoming Tiffany & Co at 550 Broadway; Ball Black & Co (formerly Ball Tompkins & Black until 1852) moved from 247 Broadway to 565~567 Broadway in 1860, celebrating their grand opening in July 1861; and, Barnum's New Museum opened September 6, 1865, at 539-41 Broadway, between Spring and Prince Streets. Broadway, near Spring Street, had become a very successful shoppers paradise among the wealthy, leaving no trace of Charles Stewart's "BRANCH" store (Fig G).

In Conclusion:

Stewart's beautiful Nutmeg Grater is one-of-a-kind and therefore, very scarce. Created about 1849 or 1850, the nutmeg grater was likely a specially commissioned piece with the identity of its original owner E.C.A. now lost to time. This nutmeg grater stands as a Charles Stewart masterpiece in precious silver. As a jeweler and silver manufacturer, Charles Stewart never reached worldly recognition. He worked as a New York City jeweler and silver manufacturer for a period of 19 years before fading into total obscurity. Few of his works in silver are known, therefore any examples of his work is "rare".

REFERENCES:

1Dripps, M. City of New York Extending Northward to Fiftieth St. (Wall Map), (1852).

2Ensko, S. G. C. American Silversmiths and Their Marks III, Robert Ensko, Inc. (1948):125, 166, 236.

3Gleason's Pictorial, "St. Nicholas Hotel, New York", F. Gleason Pub. (3-12-1853): V.I:#11:161.

4Goldsborough, J. F. Silver In Maryland, Catalogue and Exhibition, Waverly Press, Inc. ISBN 0-938420-27-5 (1984):283

5 Heritage Auctions (2007).

6 McGrew. J. R. Manufacturers' Marks on American Coin Silver, Argyros Publications, Hanover, PA ISBN 0-9761453-0-8, (2004):68.

7 Militia Laws of The State Of New-York ~ First Division, "General Orders", (1854):70

8 Mitchell, A City of New-York (Atlas Map), (1846).

9 Stone, W. L. , J. History of New York City From The Discovery to the Present Day , E. Cleave, N.Y. C., (1868):Appendix~unnumbered.

10Sterling Flatware Fashions ~ Lieberman Antiques, "Silversmiths" (Stewart Makers' Marks), (2010-2020).

ADDITIONAL READING:

*ELEGANT PLATE: Three Centuries Of Precious Metals In New York City Museum Of The City Of New York-"Charles Stewart", Editor: D.D. Waters, (2000):V.II-398.

Help us find photographs of Charles Stewart, his works, his family, home or business. We would love to include these images with this research.

Is anyone wishing to share their images? Let us hear from you. Thanks you!

[KLOPFER article © May 2022]