NutmegGraters.Com

Investigation Profile # 1. :

The purpose for the examination of this nutmeg grater is to analyze its maker's mark in relationship to its general features. Characterized as a bulbous treen nutmeg grater with silver end caps, it measures 1.6 inches tall by 1.7 inches in diameter (41mm X 43 mm). Its total weight measures 40.9 grams (the silver lids being 22.4 grams). This artifact seems unique in its design.

The purpose for the examination of this nutmeg grater is to analyze its maker's mark in relationship to its general features. Characterized as a bulbous treen nutmeg grater with silver end caps, it measures 1.6 inches tall by 1.7 inches in diameter (41mm X 43 mm). Its total weight measures 40.9 grams (the silver lids being 22.4 grams). This artifact seems unique in its design.

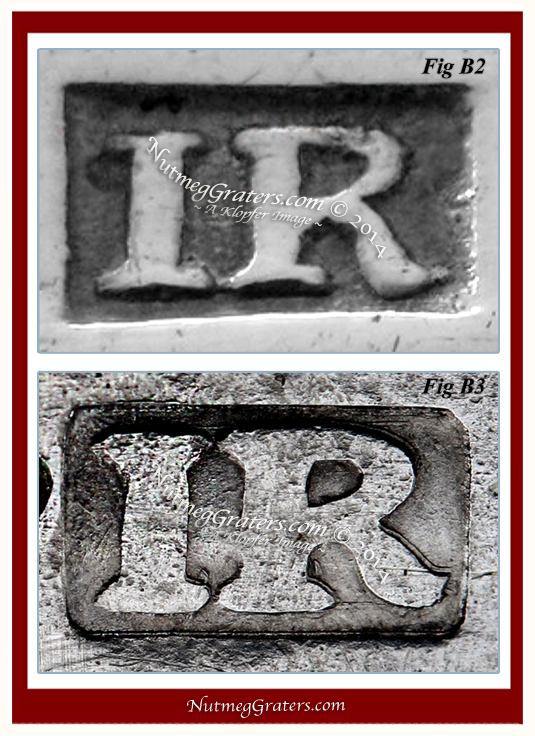

The maker's mark (Fig B3) is depicted in Roman styled initials, contained inside a rectangular outline with rounded corners. As a defining characteristic, the right descending leg on the letter "R" is shorter than its left leg.

Purchase ~ Background Information:

The treen nutmeg grater with silver caps was purchased at auction in a small lot with three other treen nutmeg graters, among a large collection of silver nutmeg graters. The May 2003 Pook & Pook Auction catalog referenced this nutmeg grater as "a silver mounted wooden circular grater by John Reily, late 19th c."

Form and Style:

This nutmeg grater appears atypical and unique in form and style. Based on nearly 40 years of research, this author knows of no similarly constructed treen nutmeg grater (however, treen nutmeg graters are not fully researched at this time). The woodworker's turning of the wood resembles methods common in the 18th to the first decade of the 19th centuries and is similar in style to turned features (legs, spindles, etc.) decorating 18th century English William & Mary or American colonial furniture.

One silver lid was formed into a rough grating surface by perforating the silver in concentric circle (Fig A1). A silver grating surface is an unusual feature, typically dating prior to Circa 1750. The second lid can be opened via a sliding tab with thumb piece (Figs A2 & A3). The sliding tab allows a nutmeg to be stored inside. A maker's mark "I R"(Figs A1 & B3) is impressed on the under surface of the sliding tab.

Review of the Literature and A Comparison Between "Maker's Marks":

The maker's mark "I R" is known to represent several silversmiths. Considered here are two makers:

~ John Reily (. . . ~1826) of London.

~ Joseph Richardson Sr. (1711~1784) of Philadelphia.

John Reily was a London "smallworker" in silver. His first maker's mark was registered in November 1799 (Fig B1). He officially entered 5 variations in marks. Reily was a prolific  maker of nutmeg graters and kitchen graters, who created a variety of forms in sophisticated and elegant styles of his era. Known example of his nutmeg graters date from 1799 to 1825 and all of his products seem to bear full sets of English hallmarks. None of his documented nutmeg graters are in the primitive style of the nutmeg grater under analysis here. Reily died in 1826. [In part: from Grimwade 3rd Edition]. Currently, the "I R" mark on the nutmeg grater under study does not match any authenticated example of the John Reily maker's marks.

maker of nutmeg graters and kitchen graters, who created a variety of forms in sophisticated and elegant styles of his era. Known example of his nutmeg graters date from 1799 to 1825 and all of his products seem to bear full sets of English hallmarks. None of his documented nutmeg graters are in the primitive style of the nutmeg grater under analysis here. Reily died in 1826. [In part: from Grimwade 3rd Edition]. Currently, the "I R" mark on the nutmeg grater under study does not match any authenticated example of the John Reily maker's marks.

Joseph Richardson Sr. was a prominent American silversmith and much is known about his work. His records are well researched and it is known that he (and men whose work he commissioned) produced pocket nutmeg graters. Richardson (and later, his sons) created their tear-drop form nutmeg grater. Currently, none of the earlier products are documented to exist. In Joseph Richardson and Family Philadelphia Silversmiths by Martha Gandy Fales, maker's marks for Joseph Richardson Sr. and his sons are well authenticated. Fales identifies and Circa-dates four maker's marks by Joseph Richardson Sr. In this investigation we examine his Circa 1750 example (Fig B2) for comparison with the mark found on the nutmeg grater under investigation (Fig B3), selected due to their pronounced similarities.

An Investigative Portfolio:

MAKER MARK ANALYSIS ~ A Spurious Maker's Mark.

[NOTE: Slight variations are expected when comparing the same maker's mark as applied to different silver items. The best account for this is detailed in Marks of American Silversmiths in the Ineson-Bissell Collection, Louise Conway Belden, University Press of Virginia, 1980; "Identification of Marks", Pages 21-23. The factors to account for subtle differences between marks struck using the same die include (but are not limited to): silver composition, hardness and quality; "differences in reflect wear, dirt or photographic technique"; the direction of the strike force applied by the silversmith, the amount of strike force; die slippage or lateral movement during the strike, die wear, and/or re-strike (or bounce) of the die. To determine usage of the same die, compare features of spacing, proportions, overall layout, shaping, styling, and most importantly, the identification of unique die flaws and shaping features of lettering and characters.]

[NOTE: Photographing a maker's mark: a Canon MP-E-65 mm lens allows for a super-macro image (extreme close-up) which shows exceptional detail when viewing an original image on a high definition monitor/screen. The detail in images using the Canon MP-E-65 lens captures a high resolution photograph in magnificent quality. For example, this lens captures the image of one third of the tip of a pencil point to yield a high resolution image as large as 40 inches by 40 inches (100 cm X 100 cm). When viewing images throughout this website, keep in mind that by reducing resolution required for an ink-jet printer (at 300 DPI), the image quality is lessoned to only satisfactory image quality, and for a website (at 72 DPI) the image quality details are significantly lessoned to fair or marginal qualities. The actual Direct Visual Comparison between "Marks" was conducted using the highest resolution images available.]

[NOTE: Photographing a maker's mark: a Canon MP-E-65 mm lens allows for a super-macro image (extreme close-up) which shows exceptional detail when viewing an original image on a high definition monitor/screen. The detail in images using the Canon MP-E-65 lens captures a high resolution photograph in magnificent quality. For example, this lens captures the image of one third of the tip of a pencil point to yield a high resolution image as large as 40 inches by 40 inches (100 cm X 100 cm). When viewing images throughout this website, keep in mind that by reducing resolution required for an ink-jet printer (at 300 DPI), the image quality is lessoned to only satisfactory image quality, and for a website (at 72 DPI) the image quality details are significantly lessoned to fair or marginal qualities. The actual Direct Visual Comparison between "Marks" was conducted using the highest resolution images available.]

(I). Direct Visual Comparison of "Marks" using photographic images:

Furnished a confirmed image of the Joseph Richardson Sr. Circa 1750 maker's mark (Fig B2), a direct visual comparison was contrasted against the Canon MP-E-65 image of the maker's mark under investigation (Fig B3). Confirmed examples of this Joseph Richardson Sr. Circa 1750 maker's marks were acquired from multiple sources [including Winterthur's Decorative Arts Photographic Collection (DAPC), a collection containing abundant materials pertaining to all of the Richardson family "marks"].

Viewed by eye, these tiny marks may appear surprisingly similar, but under Direct Visual Comparison using high definition images, significant differences become apparent. Contrasting these two marks, notice that the letter "I" (Fig B3) has crudely shaped terminals [A.K.A. extension or serif] at the top (the arm) and the bottom (the leg). With the letter "R" (Fig B3), the opened center (the bowl) is crudely misshaped. Most distinctive is that with the "confirmed mark" (Fig B2), the right leg of the letter "R" descends longer than its left leg, but with the "mark under study" (Fig B3), the right leg of the letter "R" is shorter than its left leg.

(II). Expert Testimony:

A long standing, internationally known, American silver dealer from Portsmouth, New Hampshire (requested his name not to be used publicly) examined the maker's mark on the nutmeg grater. Being familiar with the mark, he quickly identified that "I recognize this mark. Although intended, this is not the genuine mark of Joseph Richardson Sr." He identified the mark as spurious, pointing out that letter "R" displays that the "leg is shorter on its right side."

Further, Martha Gandy Fales reported, "...such a large number of spurious marks have been created and attributed to the Richardsons ... (i)n 1938 John Marshall Phillips pointed out that Joseph Richardson was among those American goldsmiths whose work has been faked in greatest quantity." [ See: Joseph Richardson and Family Philadelphia Silversmiths, Martha Gandy Fales, 1974, page 74.] Fales continues, "The suspect marks are usually characterized by a lack of skill in the  cutting of the die resulting in the letters being crudely cut, uneven, and disproportionate in that the letters are too tall and thin or too short and thick." [page 75.] Most conspicuous is the mark where the right leg of the letter "R" is short and does not extend below the rest of this letter.

cutting of the die resulting in the letters being crudely cut, uneven, and disproportionate in that the letters are too tall and thin or too short and thick." [page 75.] Most conspicuous is the mark where the right leg of the letter "R" is short and does not extend below the rest of this letter.

(III). Wood Identification: "elm":

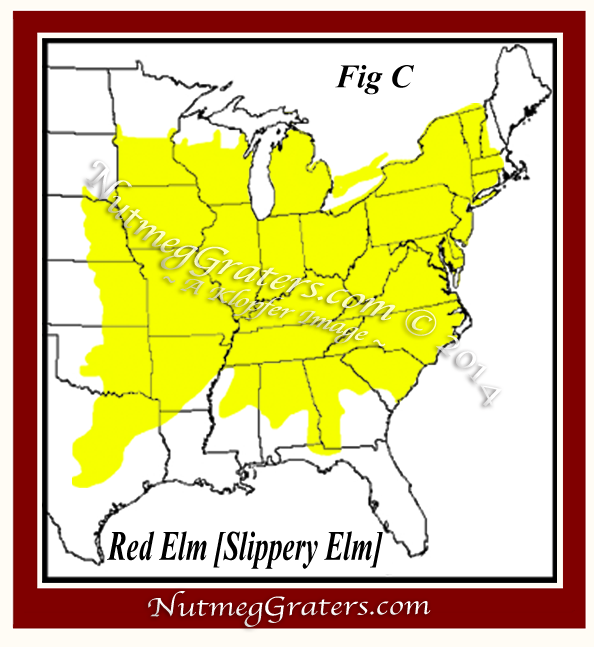

Dr. R. Bruce Hoadley conducted analysis on this nutmeg grater to determine the type of wood used to construct its body. Dr. Hoadley is a professor of Building Materials and Wood Technology in the Department of Natural Resources Conservation at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He specializes in wood identification and wood properties, and is author of the acclaimed texts: Identifying Wood and Understanding Wood: A Craftsman's Guide to Wood Technology. Dr. Hoadley conducted an extensive analysis, identifying wood in Yale's Garvin Collection of American Furniture. Regarding the nutmeg grater, Dr. Hoadley determined the wood as "elm" and informed that "in absence of other tree properties, the majority of elm tree species, worldwide, are indistinguishable by analyzing wood grain cellular patterns alone". Based on cellular patterning, he concluded the wood was not the distinctive "American Elm" variety. The wood is typical of the American "red elm" (a.k.a.: slippery elm) and several other European varieties. "Red elm" ("slippery elm") is indigenous to the Eastern-Central United States (Fig C), suggestive of a possible origin from a Mid-Atlantic Colony (perhaps Philadelphia).

When compared to the broad spectrum of treenware, the use of elm, as seen with this nutmeg grater, is an unusual feature. Because elm is known to split, it is not customarily utilized in creation of turned treenware. [NutmegGraters.Com remains interested to locate from our readers any similar treen nutmeg graters in "elm", so please share with us.]

(IV). Energy Dispersive X-ray Fluorescence Analysis (ED-XRF):

Dr. Jennifer L. Mass, Ph.D., of Scientific Analysis of Fine Art, LLC and formerly, the Senior Scientist for Winterthur Museum, conducted x-ray fluorescent analysis on this nutmeg grater to measure the presents of its metal elements and the "fineness" of its silver content. "It is thought that the mark might be spurious, and analysis was conducted to determine if the alloy of the piece is period appropriate." Early "silver" [Ag] contained impurities such as "gold" [Au] and "lead" [Pb] which, after 1840 ~ 1860, were fully extracted during the refinement process of silver. Therefore, identifying these impurities indicates that an item's fabrication was prior to this time. Secondly, the degree of "fineness" (or, percentage of silver verses other metals) in antique silver varies among different countries and aides to support knowledge of its place of origin. Two test spots were sampled as follow:

WOOD AND SILVER GRATER marked "I R"

[Test Spot #1] (Underside) [Test Spot # 2]

| ELEMENT | CONCENTRATION |

|---|---|

| Ag La1 | 86.6 wt. % |

| Cu Ka1 | 11.5 |

| Au La1 | 0.14 |

| Pb La1 | 0.17 |

| Ag Ka1 | 88.2 |

| ELEMENT | CONCENTRATION |

|---|---|

| Ag La1 | 91.3 wt. % |

| Cu Ka1 | 9.1 |

| Au La1 | 0.1 |

| Pb La1 | 0.5 |

| Ag Ka1 | 89.9 |

Based on copper [Cu], gold [Au] and lead [Pb] concentrations, this nutmeg grater is made from period silver [Ag], with the "fineness" being that of coin silver. This "fineness" quality is not typical of silver items from England or the other European countries where nutmeg graters were produced. The coin silver composition is unquestionably consistent with American silver.

Investigation Outcome:

Based on the results from an investigative profile, this uniquely styled nutmeg grater appears to bear a "spurious maker's mark"; purportedly attributed to Joseph Richardson Sr. of Philadelphia (1711~1784). Not withstanding the forged "I R" maker's mark, the genuine silversmith who originally created this item, remains "unknown".

The nutmeg grater's perforated grating surface in silver (not being iron) is characteristic of a nutmeg grater constructed prior to Circa 1750. The "fineness" quality, being "coin silver", is typical of American silver prior to Circa 1860. The wood is a non-distinctive variety of elm, possibly, but not conclusive, of the American "red elm" (a.k.a.: slippery elm). Although elm is not typically selected for "wood turning", this turned styling is consistent with furniture features from the mid-eighteenth century and reflects the construction methods for that period.

The nutmeg grater is attributed as an mid-eighteenth century American example, being the work of an unknown maker.

[KLOPFER article © September 2014]